MANAGING

gMG

Helping patients reach their generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) treatment goals

Actor portrayal.

Helping patients reach their generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG) treatment goals

gMG is a chronic, unpredictable, neuromuscular autoimmune disease1

gMG is a more severe form of myasthenia gravis (MG) that has progressed beyond ocular muscle weakness. It is caused by specific autoantibodies that impair transmission at the neuromuscular junction. AChR and MuSK are key proteins affected in gMG. Up to 95% of patients with gMG present with either AChR or MuSK autoantibodies.2‑6

gMG is characterized by muscle weakness and fatigue that worsens with activity and improves with rest.1,7

Additional symptoms of gMG7:

- Ptosis

- Diplopia

- Dysphagia

- Dysarthria

- Proximal muscle weakness

- Dropped head syndrome

- Respiratory muscle weakness

- Ptosis

- Diplopia

- Dysphagia

- Dysarthria

- Proximal muscle weakness

- Dropped head syndrome

- Respiratory muscle weakness

Symptom presence and severity often fluctuate throughout the day and from one day to the next.2

Treating gMG

Conventional therapies may not completely alleviate symptoms or function loss in all patients with gMG.1

of patients with gMG experience moderate-to-severe symptoms that limit their activities of daily living despite treatment with conventional therapies.8*

Despite experiencing inadequate symptom control, patients may be hesitant to make changes to their current therapy due to9:

- Concerns about additional side effects

- Uncertainty of response to new treatment

- Time to onset of action of new treatment

“If you don’t know something is going to work, and it doesn’t work, you feel like you’ve wasted 6 months, which can be very frustrating.” – Patient advocate

Patients may also use coping strategies like long-term planning, frequent breaks, changing plans, and reducing the amount or changing the type of work they do to compensate for uncontrolled symptoms.9

For patients experiencing uncontrolled gMG symptoms, it may be time to consider treatment options beyond conventional therapy.10

Targeted therapies for gMG address the mechanism of disease10

In recent years, therapies that target the disease pathophysiology of gMG, like FcRn blockers and complement inhibitors, have begun to emerge in the gMG treatment landscape.10,11

Although more real-world experience is needed with these treatments, they have the potential to have a positive impact in the treatment of gMG.11

Based on a US-based analysis of 1140 registrants of the Myasthenia Gravis Patient Registry (MGR), at least 18 years of age with self-reported MG from July 1, 2013 to June 30, 2017.8

Treatment goals for patients with gMG

Patient treatment goals center around symptom management2:

- Reduction in fatigue or weakness

- Consistent control of disease manifestations

- Ability to return to former activities

- Remission or cure

Evaluating treatment response

Patient-reported outcome measures, like the Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL) outcome measure, can help patients keep track of their symptoms, measure treatment progress and response, and facilitate a dialogue between you and your patients to improve quality of care and help them reach their treatment goals.12

MG-ADL Outcome Measure

MG-ADL is a patient-reported outcome measure that evaluates 8 activities of daily living12,13:

- Talking

- Chewing

- Swallowing

- Breathing

- Brushing teeth or combing hair

- Rising from a chair

- Diplopia

- Eyelid droop

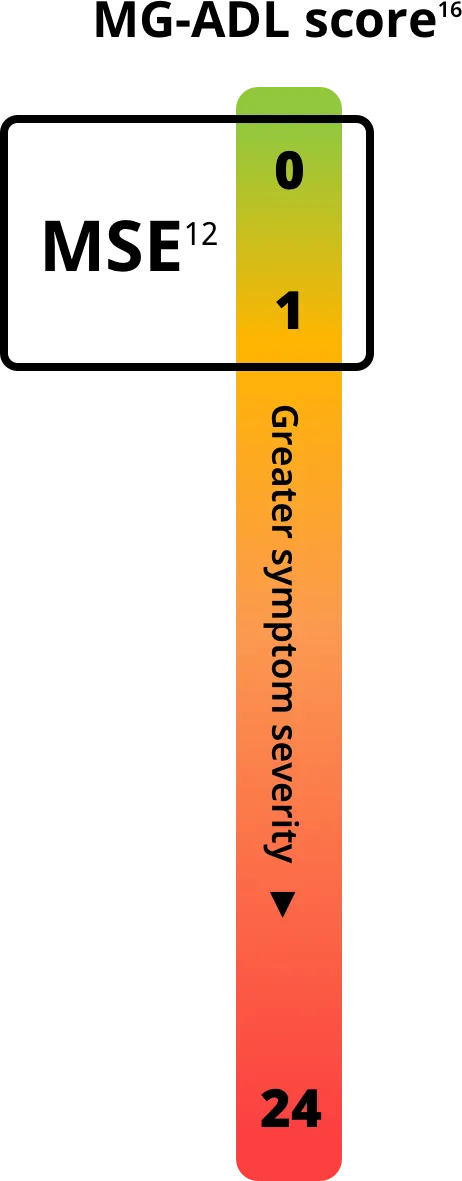

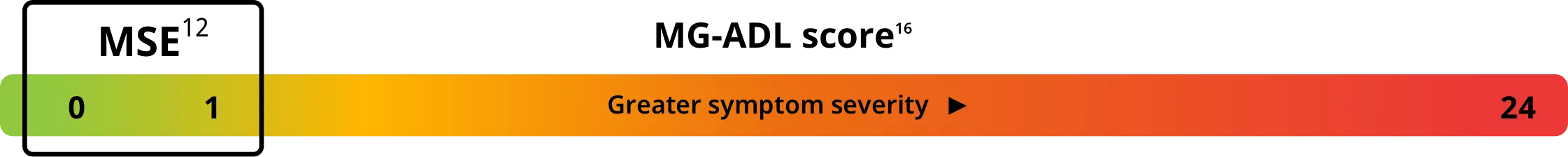

Each symptom is evaluated on a scale of 0-3, with total scores ranging from 0-24. A higher score indicates greater symptom severity.12,14

Give your patients a tool to help them track their progress and communicate their symptoms with you

Minimal Symptom Expression: a new treatment goal for gMG15

Minimal Symptom Expression (MSE) has become a treatment goal for patients with gMG in recent years.15

MSE is defined as an MG-ADL score of 0 or 1 and is a useful tool to measure treatment effectiveness.12

AChR=acetylcholine receptor; FcRn=neonatal Fc receptor; MuSK=muscle-specific tyrosine kinase.

References:

- Bril V, Drużdż A, Grosskreutz J, et al. Safety and efficacy of rozanolixizumab in patients with generalised myasthenia gravis (MycarinG): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, adaptive phase 3 study. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(5):383-394. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00077-7

- Jackson K, Parthan A, Lauher-Charest M, et al. Understanding the symptom burden and impact of myasthenia gravis from the patient's perspective: a qualitative study. Neurol Ther. 2023;12(1):107-128. doi:10.1007/s40120-022-00408-x

- Menon D, Barnett C, Bril V. Novel treatments in myasthenia gravis. Front Neurol. 2020;11:538. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.00538

- Menon D, Bril V. Pharmacotherapy of generalized myasthenia gravis with special emphasis on newer biologicals. Drugs. 2022;82(8):865-887. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01726-y

- Wolfe GI, Ward ES, de Haard H, et al. IgG regulation through FcRn blocking: a novel mechanism for the treatment of myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Sci. 2021;430:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.118074

- Gambino CM, Agnello L, Ciaccio AM, et al. Detection of antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor in patients with myasthenia gravis: a comparison of two enzyme immunoassays and a fixed cell-based assay. J Clin Med. 2023;12(14):4781. doi:10.3390/jcm12144781

- Trouth AJ, Dabi A, Solieman N, et al. Myasthenia gravis: a review. Autoimmune Dis. 2012;2012:1-10. doi:10.1155/2012/874680

- Cutter G, Xin H, Aban I, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of the Myasthenia Gravis Patient Registry: disability and treatment. Muscle Nerve. 2019;60(6):707-715. doi:10.1002/mus.26695

- Law N, Davio K, Blunck M, et al. The lived experience of myasthenia gravis: a patient-led analysis. Neurol Ther. 2021;10(2):1103-1125. doi:10.1007/s40120-021-00285-w

- Nair SS, Jacob S. Novel immunotherapies for myasthenia gravis. Immunotargets Ther. 2023;12:25-45. doi:10.2147/ITT.S377056

- Mahic M, Bozorg AM, DeCourcy JJ, et al. Physician-reported perspectives on myasthenia gravis in the United States: a real-world survey. Neurol Ther. 2022;11(4):1535-1551. doi:10.1007/s40120-022-00383-3

- Muppidi S, Silvestri NJ, Tan R, et al. Utilization of MG-ADL in myasthenia gravis clinical research and care. Muscle Nerve. 2022;65(6):630-639. doi:10.1002/mus.27476

- MG activities of daily living (MG-ADL) profile. Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. 1997. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://myasthenia.org/Portals/0/ADL.pdf

- Dewilde S, Janssen MF, Tollenaar NH, et al. Concordance between patient- and physician-reported Myasthenia Gravis Activities of Daily Living (MG-ADL) scores. Muscle Nerve. 2023;68(1):65-72. doi:10.1002/mus.27837

- Uzawa A, Ozawa Y, Yasuda M, et al. Minimal symptom expression achievement over time in generalized myasthenia gravis. Acta Neurol Belg. 2023;123(3):979-982. doi:10.1007/s13760-022-02162-1

- Regnault A, Morel T, de la Loge C, et al. Measuring overall severity of myasthenia gravis (MG): evidence for the added value of the MG Symptoms PRO. Neurol Ther. 2023;12(5):1573-1590. doi:10.1007/s40120-023-00464-x